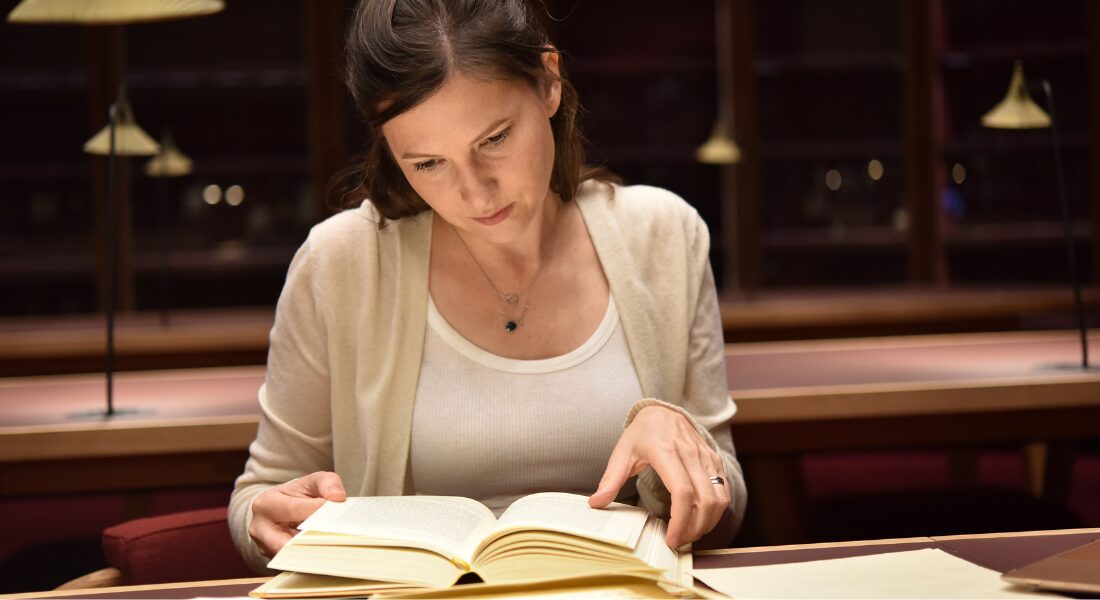

Nine years ago, after her grandfather passed away in Vienna, Dana Rubinstein sorted through his substantial library. Among the stacks of volumes, Rubinstein came upon an original 1889 Bible, translated into German by rabbi and author Ludwig Philippson. Sticking out of the pages of the well-worn volume were neatly folded tissues indicating passages that Rubinstein’s grandfather had marked for himself. As Rubinstein continued sorting, she came upon the Herxheimer translation, and then the Zunz translation. In all, Rubinstein found five different Bible translations, all bookmarked with tissues.

This was puzzling: Rubinstein’s grandfather was fluent in Hebrew and well-versed in the Hebrew Bible. Why did he own and use a Bible translation, let alone five?

When Rubinstein thought about it, though, it made sense. “He didn’t use them as translations,” she says, “at least not in the conventional sense, but as intricate commentaries, new windows into a text that was meaningful and beloved to him.”

The experience in her grandfather’s library inspired Rubinstein to reimagine the humble Bible translation — essentially the lens through which we view much of the Judeo-Christian story — in an entirely fresh way.

Rubinstein is a PhD candidate in the Department of Jewish Thought at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and an Azrieli Graduate Studies Fellow. She says translations offer readers more than just access to the Bible in their native language. When used correctly, they can help readers, even those who can read the Hebrew original, achieve a more profound understanding of the text.

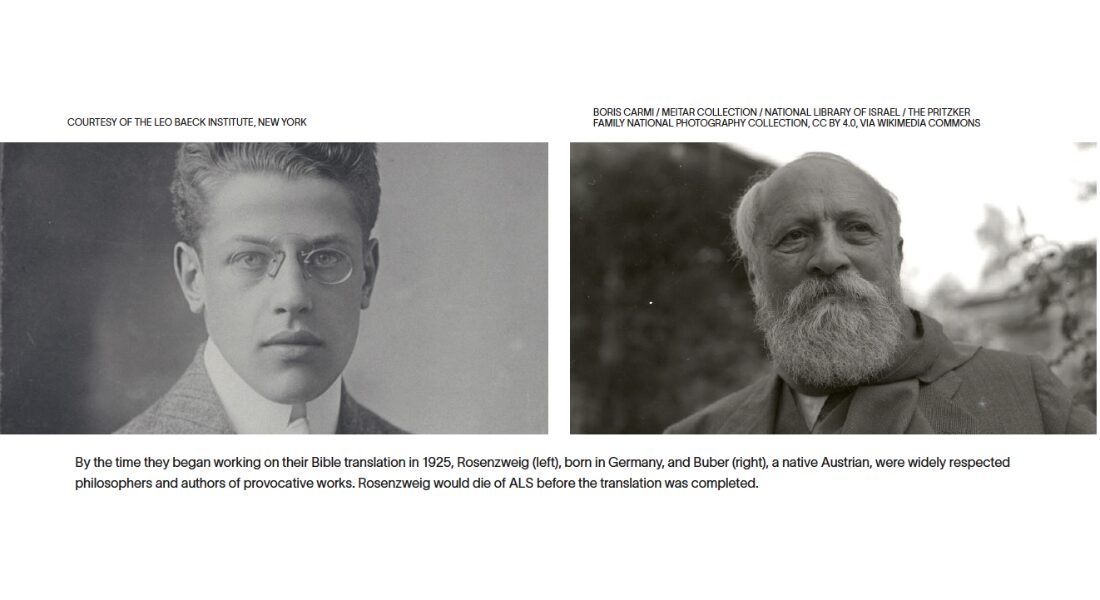

Rubinstein’s research focuses on one of the most remarkable Bible translations of all time — the German translation by philosopher-titans Martin Buber and Franz Rosenzweig. Buber and Rosenzweig were already well established as paradigm-shifting Jewish thinkers when they teamed up in 1925 to begin translating the Bible into German. They left behind some 5,000 pages of letters and drafts of the project, now housed in the National Library of Israel. It’s a tantalizing collection that allows a researcher such as Rubinstein to, essentially, eavesdrop on five years of intense dialogue and debate between the two thinkers.

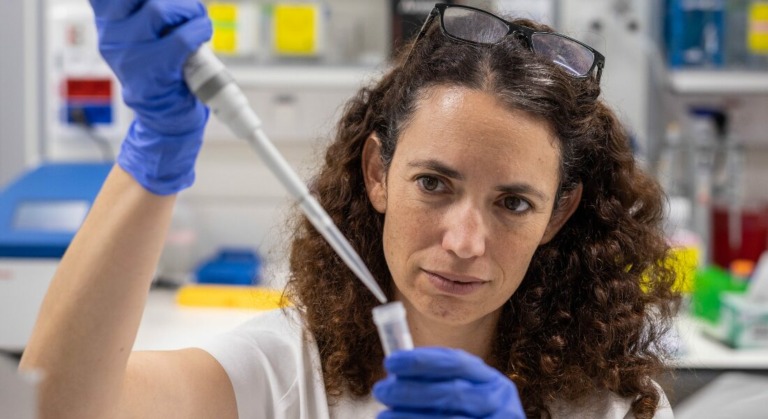

In many respects, Rubinstein is ideally positioned for this pursuit, though she did not arrive at it directly. Born in Tel Aviv and having grown up in Munich, Vienna and New York, she is fluent in Hebrew, German and English. She studied philosophy as an undergraduate at Yale University but then took a detour, earning a law degree and working in a Manhattan law firm. With the arrival of her first child, Rubinstein and a friend launched a brand of natural baby products. All the while, she became increasingly absorbed in the study of Jewish texts.

When Rubinstein and her family moved back to Israel, she resumed her academic career at Hebrew University. She first worked with the Buber-Rosenzweig papers while completing a master’s thesis on Bible scholar Nechama Leibowitz.

Benjamin Pollock, her PhD supervisor at Hebrew University, describes Rubinstein as a “one-of-a-kind doctoral student” with “a combination of philosophical and hermeneutical sensitivity and a profound sense of responsibility to bring to light through scholarship aspects of the German-Jewish world that have been lost.”