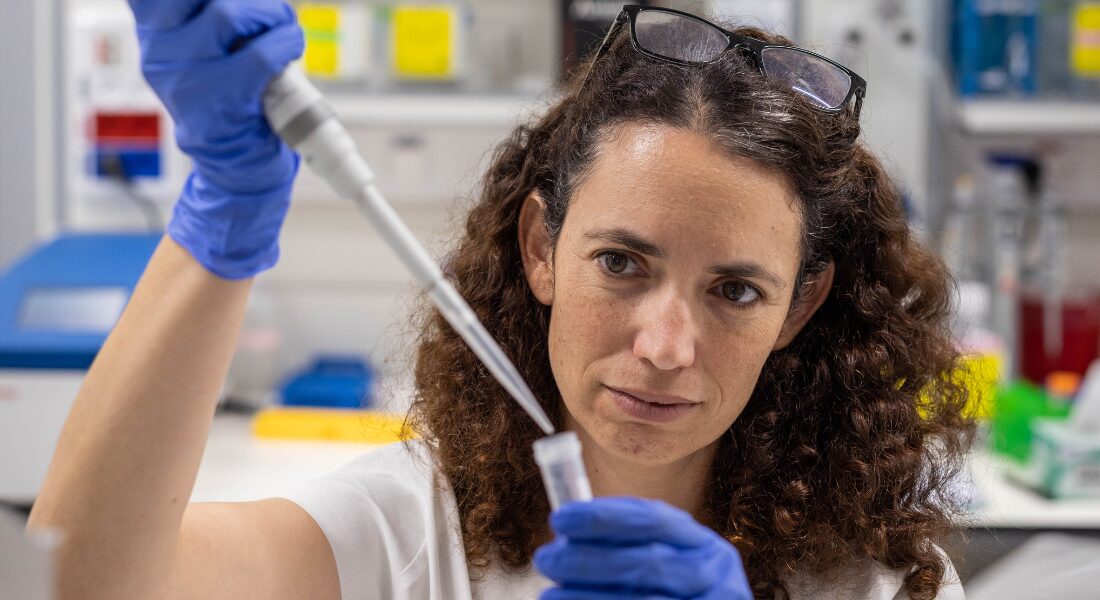

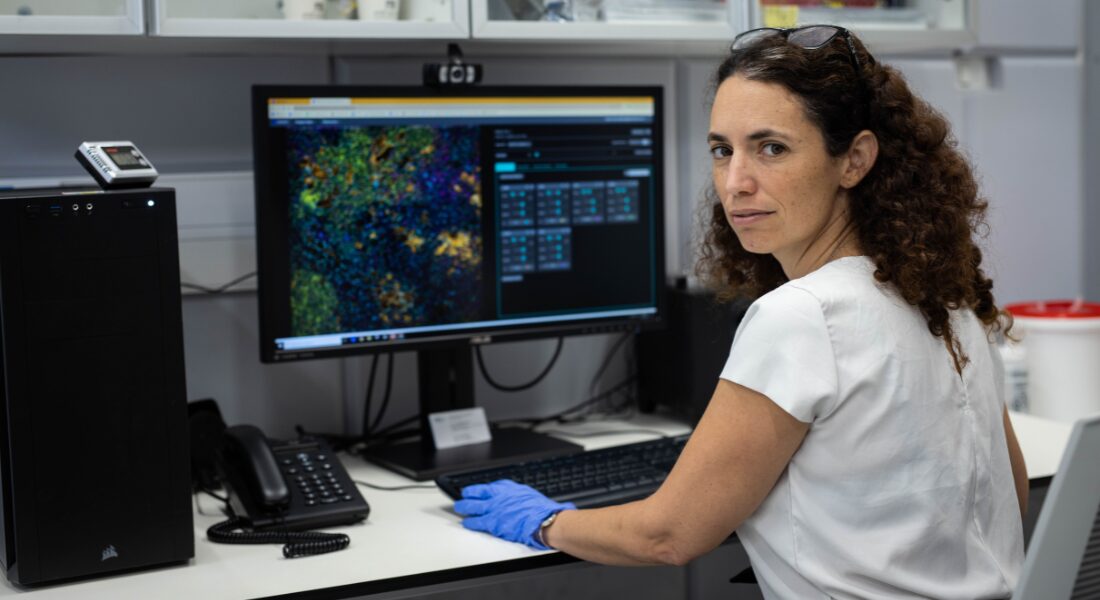

Leeat Keren was fresh from completing her PhD in computational biology at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel. As a systems biologist, she was interested in putting pieces together. She had been trained to use computers and mathematics to figure out how the genetic and molecular networks in our bodies operate together to keep us healthy or break down and cause disease.

She thought the field of immunology was primed for disruption by the systems biology approach and was emboldened while attending a presentation by Michael Angelo, a Stanford University pathologist, at an immunology conference.

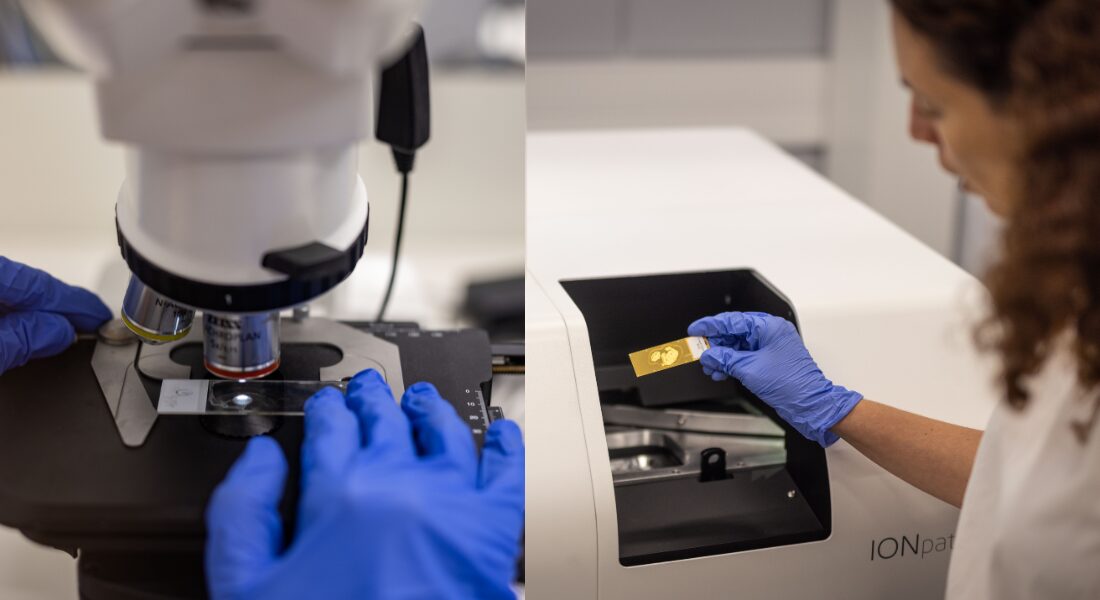

“He presented this idea of a new instrument he was building to be able to visualize many proteins inside the tissue at once without disrupting it,” Keren says. “And I remember I came back to my office and told my roommates, ‘This is what everybody is going to be doing a few years from now.’ I fell in love with this technology and the prospects of what it could do.”

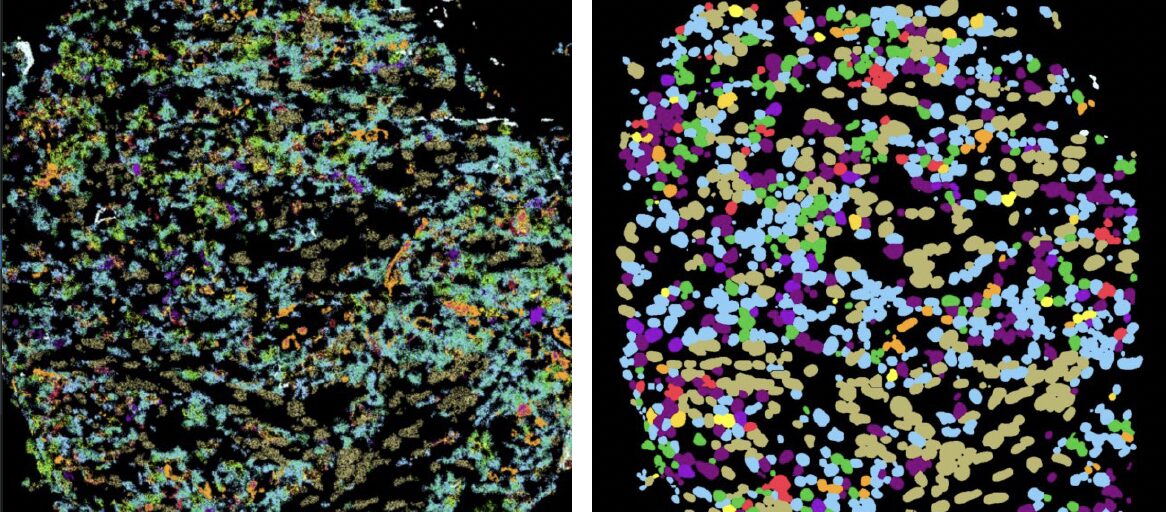

The technology is called multiplexed imaging. For more than a century, pathologists have been examining tumours by placing them under microscopes and studying the shapes of the cells and how they were organized. More recently, they have been able to do tests that reveal the genetic activity in the tumour cells and which proteins are being produced by those genes.

The trouble is that these tests require the cells to be pulled apart. Scientists see how the cells are behaving overall but lose information about how these cells communicate with each other, relate to one another, cooperate or compete.