To be human is to sleep. Also, to be human is to find yourself unable to sleep and to spend endless overnight hours reading obsessively about how chronic sleep deprivation is toxic for your brain. Every involuntary hour of wakefulness is a further strike against your cognitive function and ability to consolidate memories, regulate your emotions and repair damage to your neurons. It’s almost enough to make you wish you didn’t have a brain that could keep you awake reading about how much damage you’re doing to your brain.

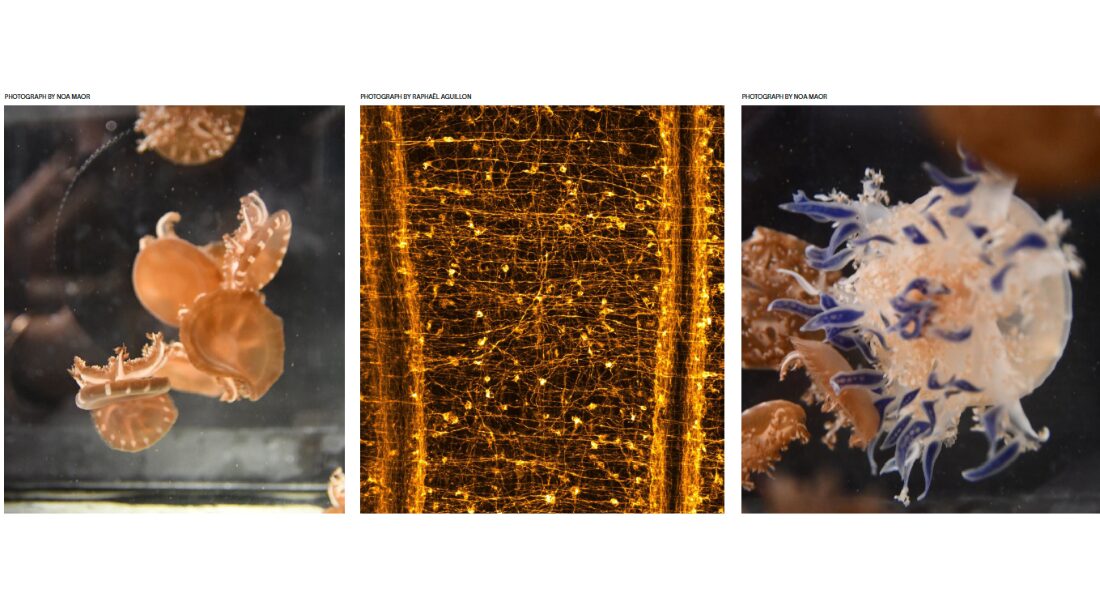

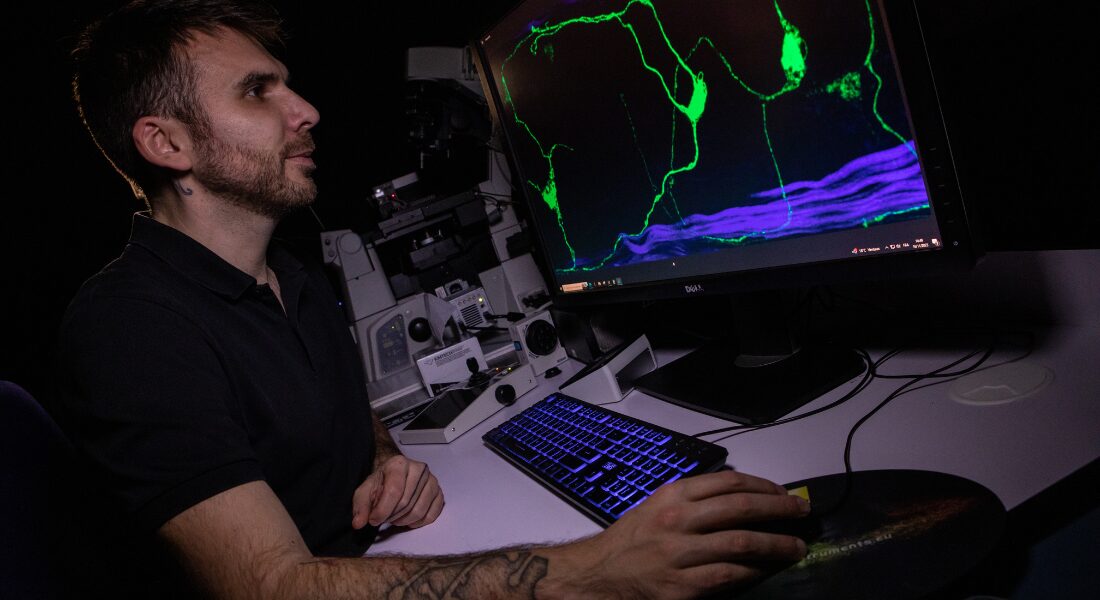

While not every animal suffers from nighttime anxiety, every species that scientists have observed experiences sleep in some fashion. By studying jellyfish and sea anemones — animals with some of the most primitive nervous systems — Raphaël Aguillon hopes to shed light on some of the fundamental questions about sleep throughout the animal kingdom.

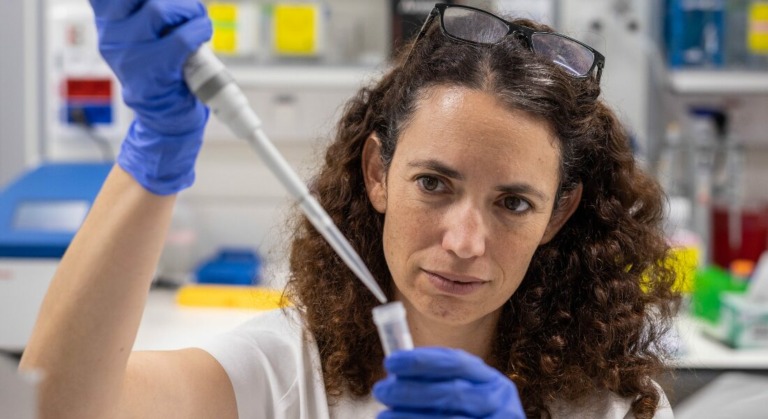

“We have a lot of hypotheses about sleep, but there’s so much that we don’t know about its functions and processes,” says Aguillon, who is pursuing research with an Azrieli International Postdoctoral Fellowship at Bar-Ilan University.

According to Aguillon, who refers to himself as a “marine chronobiologist,” scientists have been studying sleep throughout the animal kingdom for decades. From mammals to insects, sleep has been found in each kind of organism. But there’s no coherence in the quality of sleep. Some animals sleep during the day, others at night. Some sleep for long periods, others for just a couple of hours. Some sleeping animals go completely still, and some continue to move. “Whether you have a huge brain or no brain at all,” Aguillon says, “you need to sleep.”

His work on simple sea creatures has the potential to unravel some of the larger questions about sleep in general, such as how it evolved, what purpose it serves and why each species has different rhythms.

The universal animal need for sleep led Aguillon and his colleagues to ask an even more fundamental question: Which came first, sleep or the brain? In searching for an answer, Aguillon looked to the cnidarians (pronounced with a silent “c”), a phylum of invertebrate aquatic animals containing more than 10,000 species, recognizable to most of us as jellyfish, sea anemones and corals. These creatures look as if they’re not even from the same planet. They lack a brain yet have a basic nervous system that contains both excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters. Neurons communicate with neurotransmitters via electrical currents — different types of neurotransmitters.