The sudden emergence of Islam and dramatic growth of the Islamic polities known as caliphates in the seventh century CE and onward has been the source of enduring fascination. Between 634 and 644 alone, the campaigns of Caliph Umar brought Sassanid Persia and the Byzantine Empire’s territories in Egypt, the Levant and much of North Africa under Islamic rule. But the newly arrived Muslims faced an enormous challenge: How to govern vast and populous lands with well-developed Greek and Persian bureaucracies already in place?

The eventual success of the caliphates as multi-ethnic empires is vital to understanding the cultural melting pot of the medieval Middle East and the region’s subsequent development. It is a slice of history that has intrigued Eugenio Garosi since he was 18, when he travelled to Syria with family. “You could see the ruins of ancient cities, side by side with wonderful Muslim monuments, Crusader fortresses and others,” says Garosi, a historian of early Islam and former Azrieli International Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Haifa.

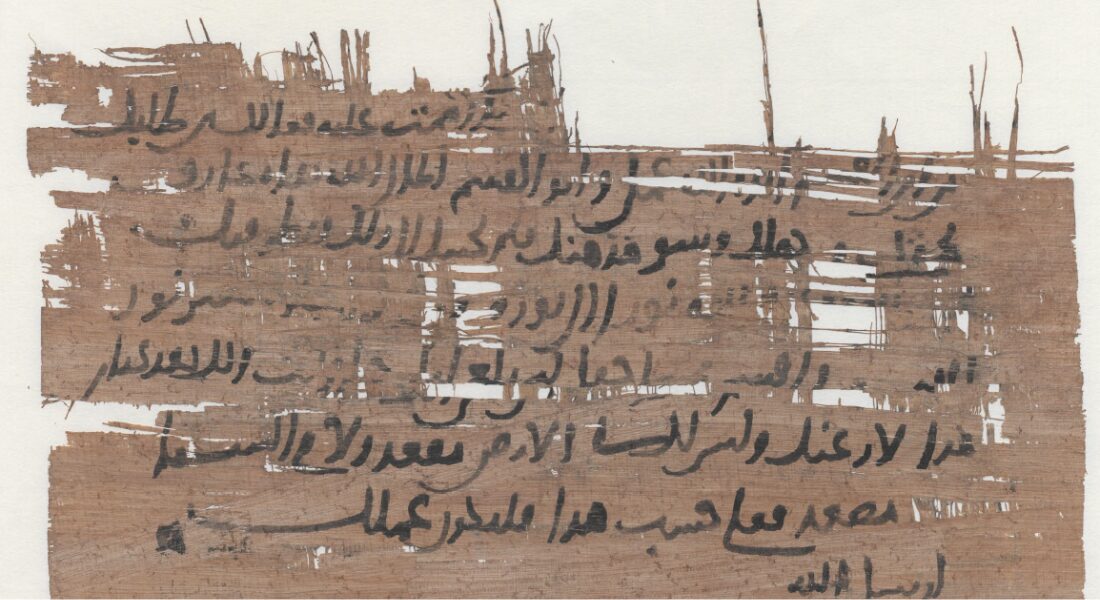

Beyond the grandeur of those ancient ruins and the sweeping narratives of empires rising and falling lies a deceptively simple layer of history: papyri from the early Islamic period. These are seemingly inconsequential documents written by people living within the caliphates, and the light they shed on their time fascinates Garosi. Each papyrus may seem to say little — a sales document here, a letter between bureaucrats there. But as Garosi looks at them together, studying the way the writers write, the language they use, even the sentences they pick, he can spot patterns that reveal the details of their lives. They speak not just to the people who wrote them, but to the complex and evolving empire in which they lived.

“From one contract of sale, you don’t gather much,” he says. “But once you try to put it within a series of parallels, you can actually get from the very small to a larger system, and you can do it from the bottom up.”

Garosi’s research focuses on scribal norms, the rules and conventions writers used while drafting letters in the early Islamic period, particularly in Egypt, where the climate allowed more papyri to survive. By piecing together volumes of these early-medieval documents and studying how scribal norms interact, his research paints a picture of cultural adaptation and change as a minority ruling class of Arabic-speaking Muslims sought to govern a new empire.

Garosi’s research approach had its roots in a conversation with a supervisor at an Ethiopian restaurant in Jerusalem, Israel. He came to realize that papyri — many of them available in online archives such as the Arabic Papyrology Database — provide a unique evidence base to move beyond biographical scholarship focused mainly on eminent scholars and leaders.

“These particular sources allow you to look at a more representative sample of society,” says Garosi. While not as broad as a modern sociological study, papyri can nevertheless be analyzed for patterns – and, in many cases, for changes in those patterns over time.