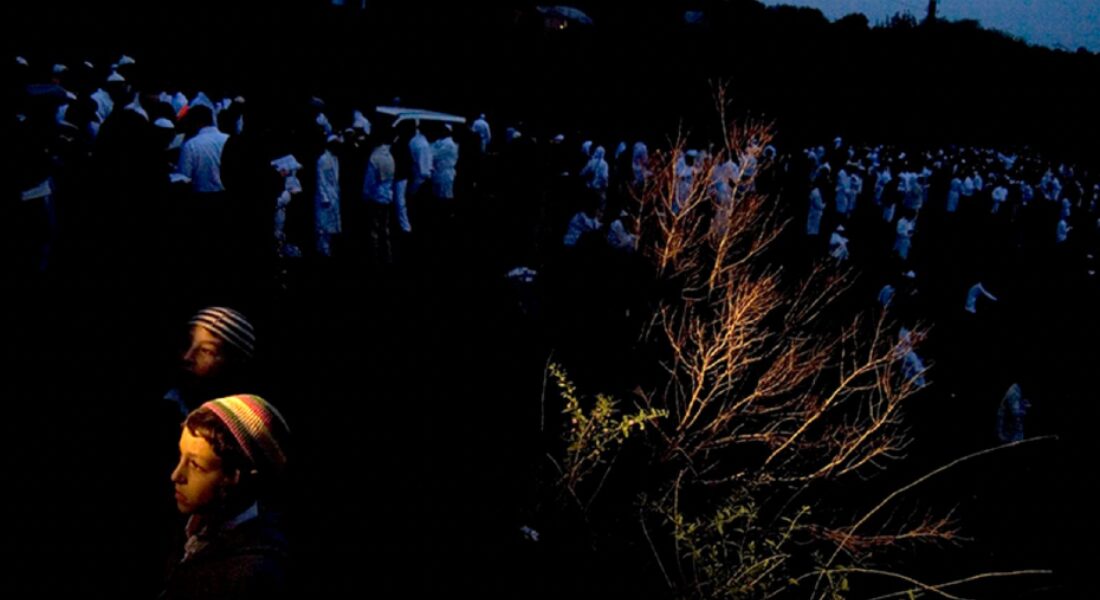

Alla Marchenko spent her childhood near Europe’s most visited Hasidic pilgrimage site, in Uman, a city of about 81,000 in central Ukraine. But, at age 16, she couldn’t wait one moment longer to explore the outside world. She embarked on a personal journey that took her to Kyiv, New York, Warsaw and Jerusalem, along the way learning English, Yiddish, Hebrew and Polish.

Marchenko’s life, it seems, has come full circle. During her five years pursuing a PhD, she studied cultural memory in places connected to Hasidic pilgrimage in Poland and Ukraine, including Uman. And she worked on numerous international projects to uncover the neglected heritage of Uman and Lviv, in western Ukraine.

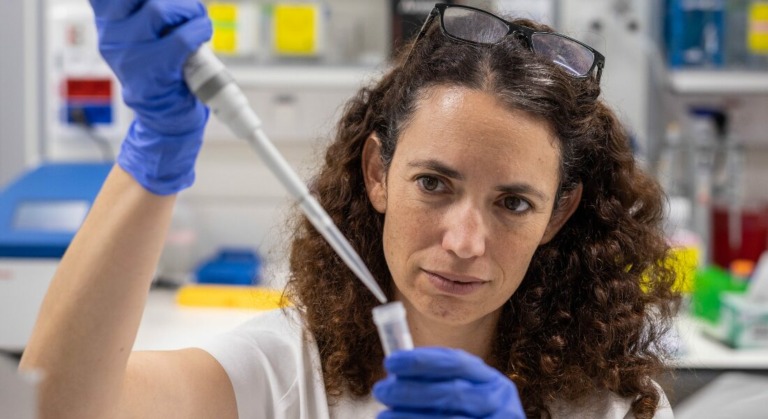

Today, Marchenko is an Azrieli International Postdoctoral Fellow in sociology and anthropology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem — and returning again and again to Polish and Ukrainian pilgrimage sites. In Polish towns of Leżajsk and Dynów and Ukrainian towns of Medzhybizh and Uman, she sees first-hand how Jewish female pilgrims navigate and make meaning in areas where they traditionally have been overlooked.

The duality of religion and female empowerment is an understudied phenomenon, and the views of religious women who have agency are rarely heard, she says. “The voice of religious women who don’t think in the dual frame of oppression and liberation is the one that is often neglected,” she says. “I try to represent this voice through the phenomenon of pilgrimages. Pilgrimages constitute a part of important religious rituals, but they also fulfil other roles along the way.”

Marchenko has been able to build trust among female religious pilgrims who are normally quite reticent. She travels to and from pilgrimage sites with them and accompanies them as they visit shrines. “Women can share their private matters with me and feel comfortable that I am also a pilgrim, not an outside scandal hunter,” she says.

The women she has met so far have been motivated to travel to Ukraine and Poland for a variety of reasons. Some pilgrims have attended to pray for a husband, fertility or good health for themselves or family. Others have searched for an elevated spiritual experience or heard stories of miracles happening at the shrine and wanted to see for themselves.