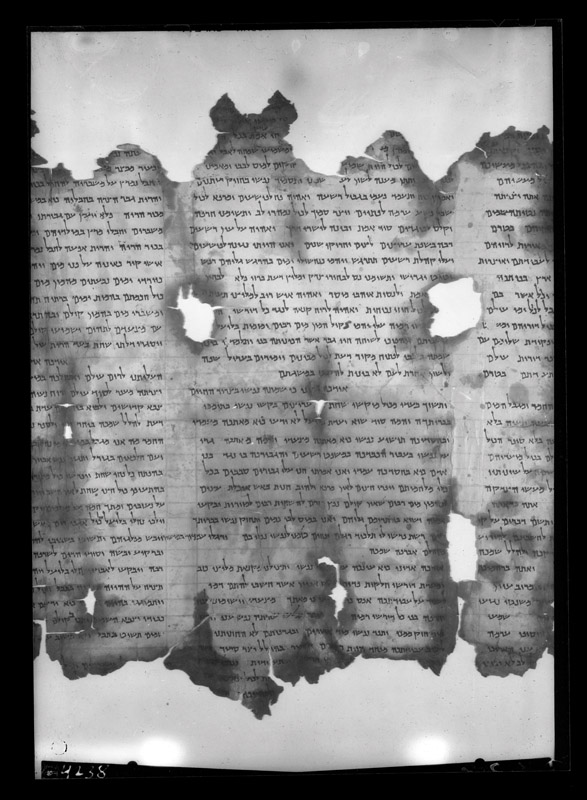

The discovery of the first seven Dead Sea Scrolls by Bedouin shepherds created an international sensation, which was compounded by the discovery over the following decade of nine more caves at Qumran containing the fragments of 950 additional Jewish and Hebrew scrolls from 445 different literary compositions. That only a handful of scrolls in this miraculous cache were intact — many were just heaps of confetti — did nothing to blunt their collective impact. These scrolls threw open a window onto a lost world of Jewish religious practice. Composed between 300 BCE and 70 CE, they fill in our picture of what was happening at a critical juncture in the development of Jewish religious traditions that would eventually feed into and shape Western worldviews, explains Johnson, whose specialty is early Judaism and psalms and prayers from the Second Temple period (515 BCE to 70 CE). “Before the Dead Sea Scrolls,” he says, “there was much less indication of how ancient Jews conceived of their scriptures as a corpus, or to what extent they were moving towards the codification of those scriptures into a formal canon resembling the Bibles we have today. It turns out that their conception of authoritative scripture was much more fluid and broader than we realized.”

Although revolutionary in content, the fragmented state of the scrolls has created an ongoing physical and interpretive jigsaw puzzle for scholars, which immediately attracted Johnson. “I started out in biblical studies,” he recalls, “and one of the first things you learn is that this material has been researched for thousands of years and it is very challenging to say something new.” Early in his graduate studies, which began at Emory University in his native United States and culminated in a PhD at McMaster University in Canada, his interest in the Hodayot began with a paper on the scroll 1QHa, which contains collections of previously unknown ancient psalms or hymns. Johnson soon learned the texts were incomplete, their interpretation uncertain and the position of the scroll fragments unsure. He grew excited by the opportunity to contribute to their refinement. The liturgical dimensions of the texts, such as the communal blessing and praise of the deity alongside the angels at the prescribed times for prayer, also drew him in because they are some of the only surviving texts illuminating these aspects of ancient Jewish religious life in this period.

The scroll 1QHa is unique because it was found in two bundles — one roughly wadded and the other more carefully folded — and is about 75 per cent complete.

Photograph copyright The Israel Museum, Jerusalem