There’s a familiar story about the history of modernity and mathematics — a story that Ray Schrire, a historian and Azrieli Early Career Faculty Fellow at Tel Aviv University, believes is mostly wrong. It goes like this: in premodern Europe, people practised premodern math. Merchants and shopkeepers managed their books with Roman numerals, but these weren’t numbers, at least as we understand them. They were more like codes or coordinates — a set of instructions that would tell you how to move beads around on an abacus or slide a token around a table.

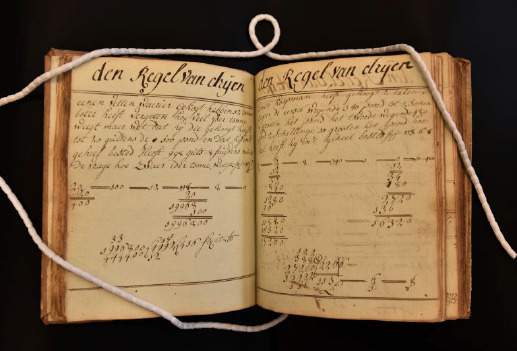

For the average bookkeeper, mathematics was less a system of abstract thought than a set of practices. If you kept diligent records and used your abacus well, you could perform basic calculations and get the results you were seeking. But people had limited insights into what they were doing: performing calculations is different from understanding them. And medieval practitioners couldn’t get their heads around exponents, infinite series or negative numbers. Tellingly, there is no Roman numeral for zero. Why would there be? You can’t move zero beads from one abacus rung to another.

In the early-modern era (the period beginning in the late 15th century and ending with the dawn of the 18th century), everything changed, or so the story goes. Europeans abandoned Roman numerals for the Hindu-Arabic notational system we still use today, and they adopted written arithmetic, a practice imported from the Middle East. Some of the smartest thinkers in the West — Isaac Newton, Blaise Pascal, Gottfried Leibniz — began pushing mathematics into abstract territory, inventing entire disciplines that hadn’t existed before. And thanks to the advent of global capitalism, members of the European professional classes suddenly found themselves calculating dividends, compound interest rates and insurance premiums. These new ideas quickly proliferated, making ordinary working people more sophisticated, more capable of abstract thought — in a word, more modern — than their medieval forebears had been. A commercial and industrial revolution gave rise to a cognitive one.

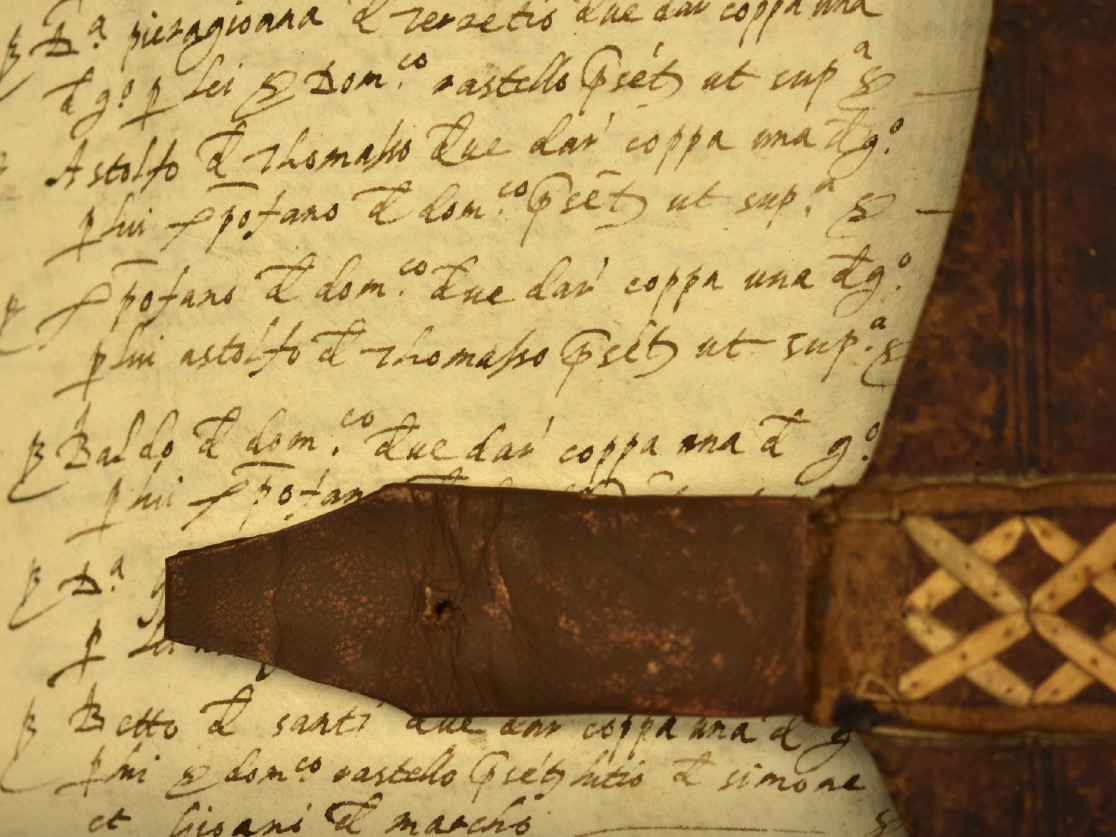

Or did it? Schrire isn’t convinced. He has studied the documents left behind by early-modern professionals — poring over account books and bills of sale from merchants, shopkeepers, land surveyors and notaries — and been surprised by what he found. Or rather, what he didn’t find.