For somebody with depression, everyday life can be a struggle. It is among the most common mental health disorders worldwide, affecting more than 280 million people. Depression can negatively impact personal relationships and work performance. In severe cases, it can be debilitating and contribute to suicide.

Depression is commonly treated with a class of antidepressants called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). These drugs have been in use since the 1980s and have helped countless patients cope, but their side effects can make them intolerable. And even though SSRIs have been around for decades, we still don’t know much about how they actually work.

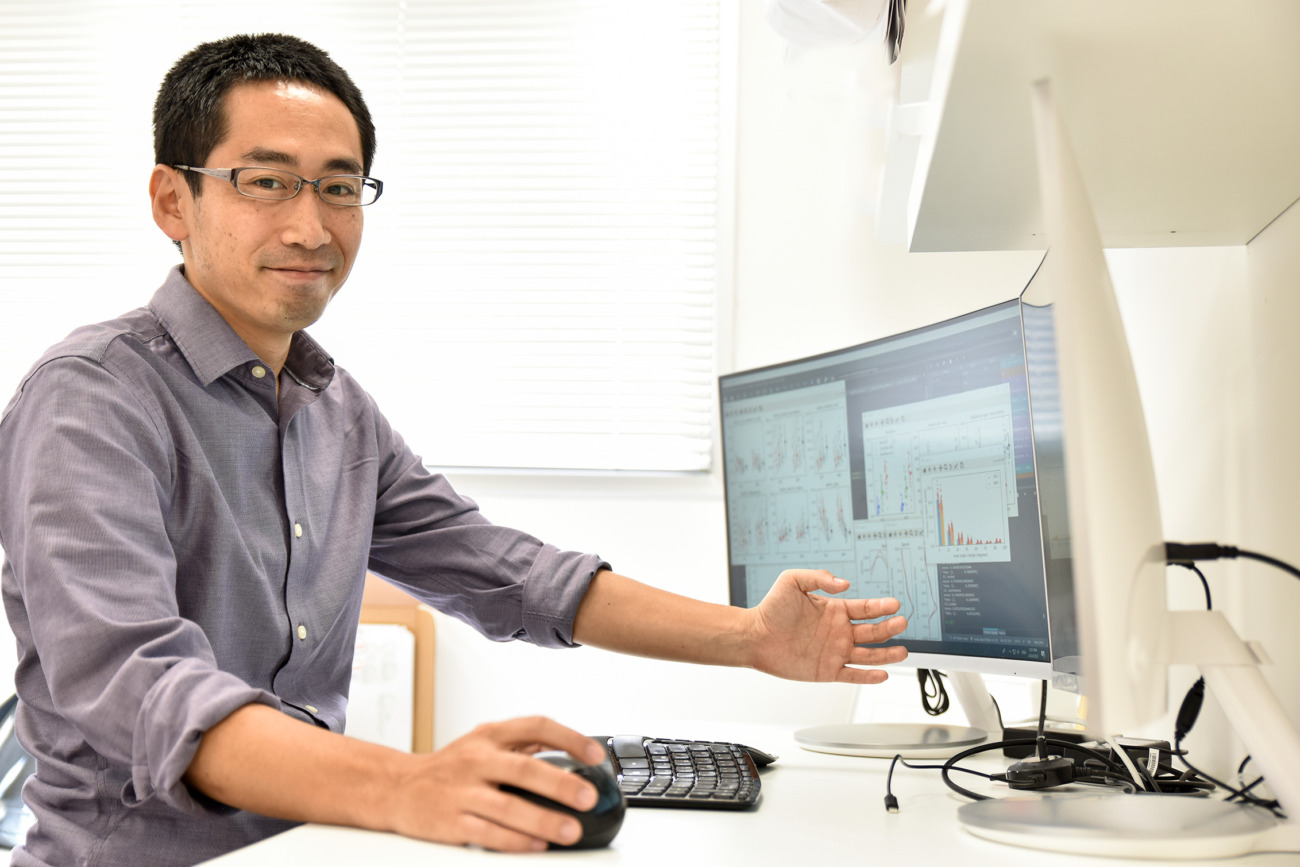

Weizmann Institute of Science neuroscientist Takashi Kawashima, who is based in the institute’s Department of Brain Sciences and was an Azrieli Early Career Faculty Fellow until 2022, is exploring whether an entirely different kind of drug could yield similar benefits, without the unintended consequences of SSRIs. His research is probing the potential of a psychoactive chemical called psilocybin, which is better known for inducing hallucinations (see “A Brief History of Psilocybin,” below). Kawashima is investigating whether psilocybin can mimic serotonin’s effects in the brain and, if so, which mechanisms it uses. In the long run, this could help lead to the development of depression treatments that are more effective and faster acting than the drugs that doctors rely on now.

Serotonin is a chemical that functions as a neurotransmitter, a kind of messenger that transmits signals. A deficit of serotonin in the brain is thought to be a major underlying factor in depression. This is called the serotonin theory of depression, and it is widely accepted, although we don’t know how serotonin deficiency actually leads to depressive symptoms.

Commonly prescribed SSRIs such as Prozac and Zoloft work by increasing the amount of serotonin in the brain. But these drugs have distinct drawbacks. In addition to mood regulation, serotonin is also involved in digestion, sleep, learning and sexual drive. When serotonin levels are increased, any of these functions can be affected. For some people, nausea and diarrhea make SSRIs intolerable.

Beyond that, SSRIs can take several weeks to have an impact. They work by blocking the brain’s reabsorption of serotonin, which increases the amount of serotonin that’s available. But this change takes time, so patients don’t immediately know whether a prescription is working, and identifying the right regimen is a trial-and-error process. It often takes months for people to find a tolerable balance between recovery from depressive mood and the side effects of SSRIs. Some never do.

Psilocybin is different. It doesn’t increase the amount of serotonin but appears to act as a serotonin mimic. Because psilocybin causes changes in the brain’s function, treatments derived from it could work more quickly than SSRIs with fewer side effects. We don’t know how psilocybin produces these effects either, but that’s one of the things Kawashima is working on. And he is using an innovative new model to understand psilocybin: the tiny zebrafish (Danio rerio).