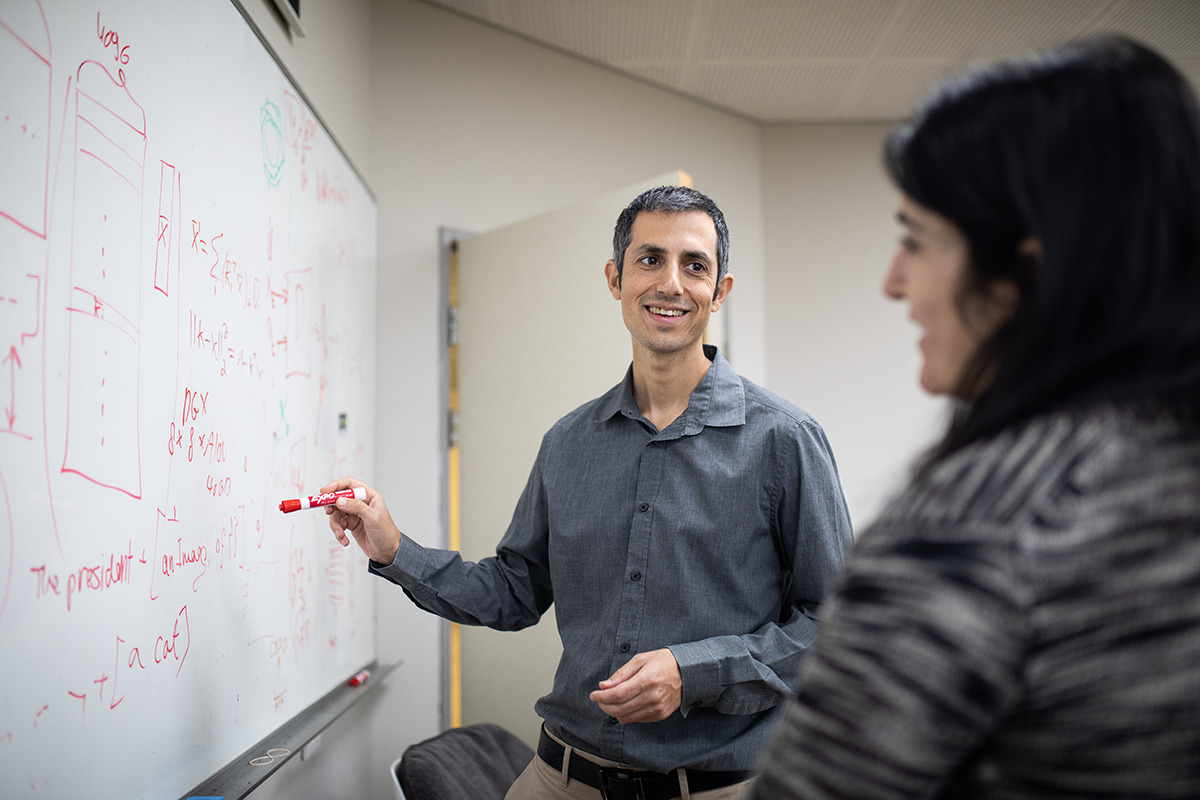

What’s it like to specialize in a branch of science that’s in the news almost every day? That’s the unusual position in which Yonatan Belinkov finds himself.

He’s an expert on artificial intelligence (AI) and natural language processing, which includes the study of large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT. Released last November by OpenAI, ChatGPT is a sophisticated chatbot that can generate text in response to just about any prompt a user gives it. The text it produces can seem very human.

But the technology has also proven controversial. On one hand, ChatGPT appears to be bolstering productivity in fields such as marketing, grant writing and data analysis. At the same time, there are concerns about its effects in schools and universities — it can produce passable undergraduate-level essays in the blink of an eye — and worries that it threatens journalism and even democracy, with its potential to flood the world with fake news.

That’s because sentences produced by ChatGPT aren’t necessarily true. Belinkov, a professor of computer science and Azrieli Early Career Faculty Fellow at Technion–Israel Institute of Technology, put the software to the test recently by asking it who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1948.

“It told me that the United Nation Committee on Civil Rights won the Nobel Prize,” he says, “and it told me why it won the Nobel Prize. It gave a very convincing answer — except that it’s false. The prize wasn’t awarded that year. Gandhi was nominated, but he was murdered just a few days before the decision, so it wasn’t awarded. But ChatGPT was very convinced.” (Cases where chatbots seem to go off the rails in this manner have been dubbed “hallucinations” and are thought to be triggered when the system strays too far from its training data.)

Falsehood is only one problem. AI language systems have also been known to perpetuate biases. For example, studies have shown that when prompted with statements such as “the nurse said that . . .” the system is more likely to complete the sentence on the assumption that the nurse is a woman rather than a man. And it found the reverse bias when prompted with the word “doctor.”

These are big changes from a decade ago, when chatbots could barely string together a coherent sentence. “In 2012, when I started my PhD, I couldn’t imagine anything like what we have today,” says Belinkov. “It’s a little challenging to be in a field that is very, very hot, because progress is so fast. Every day, there’s a new research article that I need to read. Staying up to date can be tricky.”

The key development enabling this leap forward is the rise of “deep learning” architectures known as artificial neural networks. These networks use a series of “layers” of mathematical processing to assess the information they’re fed. The connections between the layers are assigned weights that reflect the importance of each connection relative to the others, and those weights are adjusted as the network is exposed to more and more input data. Finally, the last layer produces an output. In recent years, neural networks have become proficient at recognizing faces, translating languages and, with programs such as ChatGPT, creating human-like text. (A few months ago, an even newer version, called GPT-4, was released; it can create websites in minutes, explain jokes and suggest recipes based on a photo of what’s in your fridge.)