Fifteen years ago, when she was working toward her PhD at the University of Chicago, Inbal Ben-Ami Bartal had to figure out how to stress a rat. Rummaging around among the equipment in the lab, she found a small plastic tube-shaped enclosure. To see how well it worked, she went to a cage containing rats and put one inside the tube. Sure enough, the confined rat didn’t seem to like it, squeaking and showing other signs of distress.

What surprised Bartal, however, was the reaction of the trapped animal’s unrestrained cagemate. It scampered around and dug and bit at the plastic enclosure, to all appearances trying to help the rat inside. “The cagemate started just going nuts,” she recalls. “I got really excited and said, ‘You know, this rat really seems to care that the other rat is trapped.’”

Instead of studying the rat in the tube, Bartal decided to focus on the other rat. Three years later she was the lead author on a paper in the journal Science called “Helping a cagemate in need: empathy and pro-social behavior in rats.” The paper was the first to show that rats are motivated by empathy to help others in distress and suggested that empathy’s roots extend far into the evolutionary past. It gained international attention and helped to legitimize the science of animal emotions. Just as important, Bartal’s continuing research promises to help us understand how empathy works in humans and could provide insights into everything from racism to psychopathy.

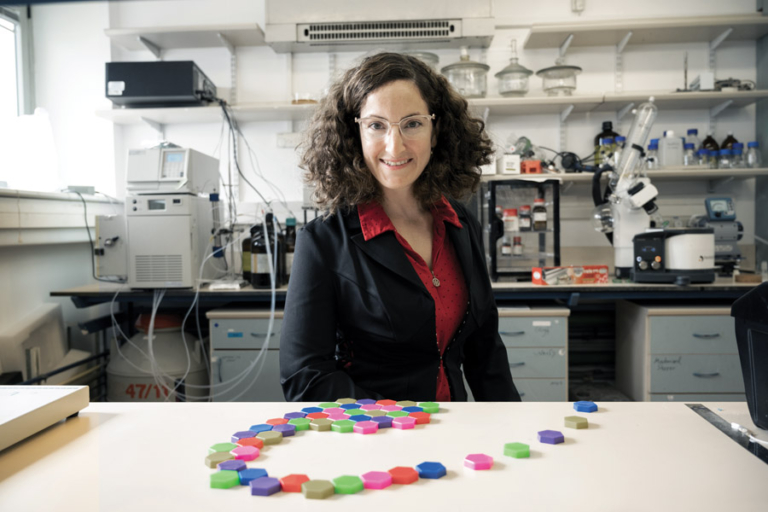

Bartal is now a faculty member in the School of Psychological Sciences and the Sagol School of Neuroscience at Tel Aviv University (TAU), where she held an Azrieli Early Career Faculty Fellowship between 2019 and 2022. After high school and her military service, she took a job at a technology company in Paris. But in her spare time she became fascinated by cognitive science and the brain. When she moved back to Israel, she won a scholarship to the Adi Lautman Interdisciplinary Program for Outstanding Students at TAU and studied neuroscience, biology and psychology. Her master’s work at TAU used rats to examine the effects of stress on the immune system. For her PhD she wanted to study complex cognitive processes and found herself again working with rats, because “humans are really, really complicated,” she says, laughing.