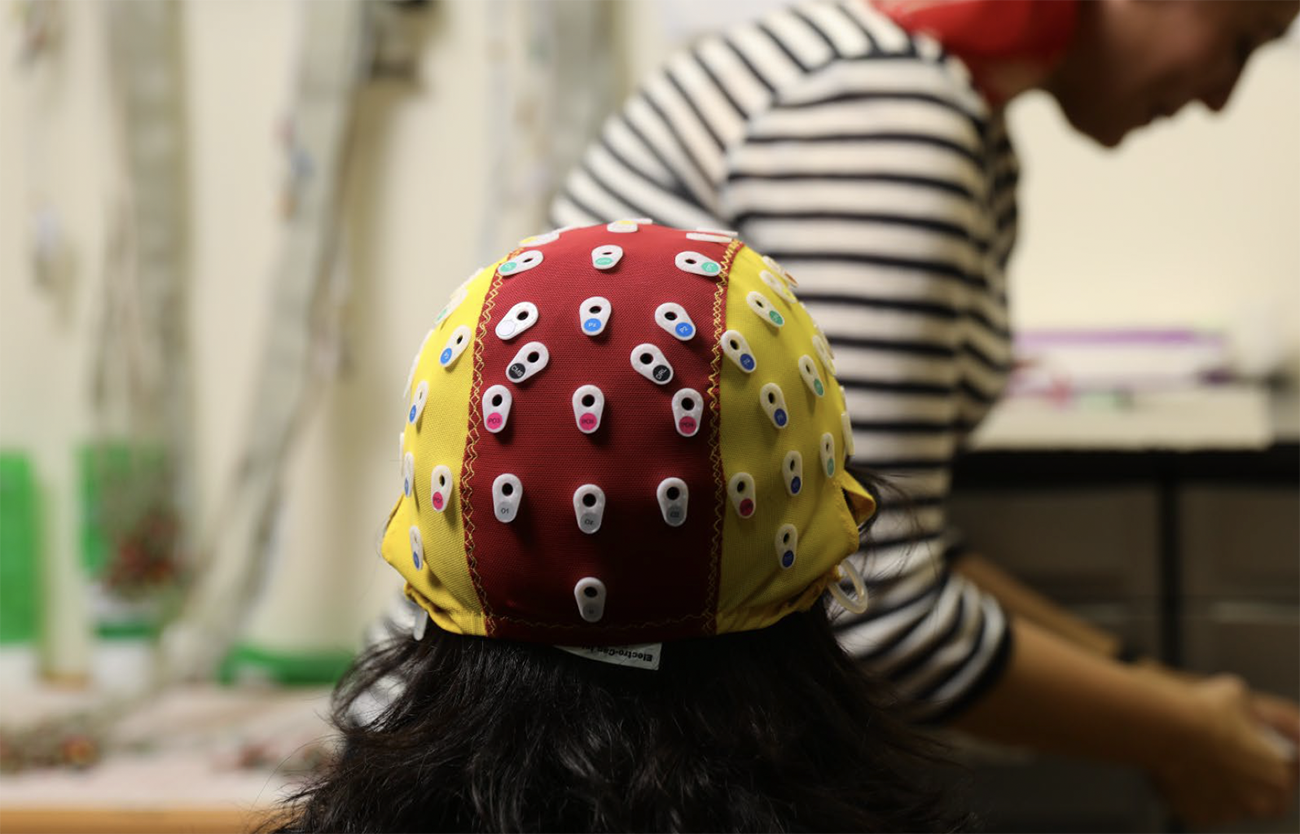

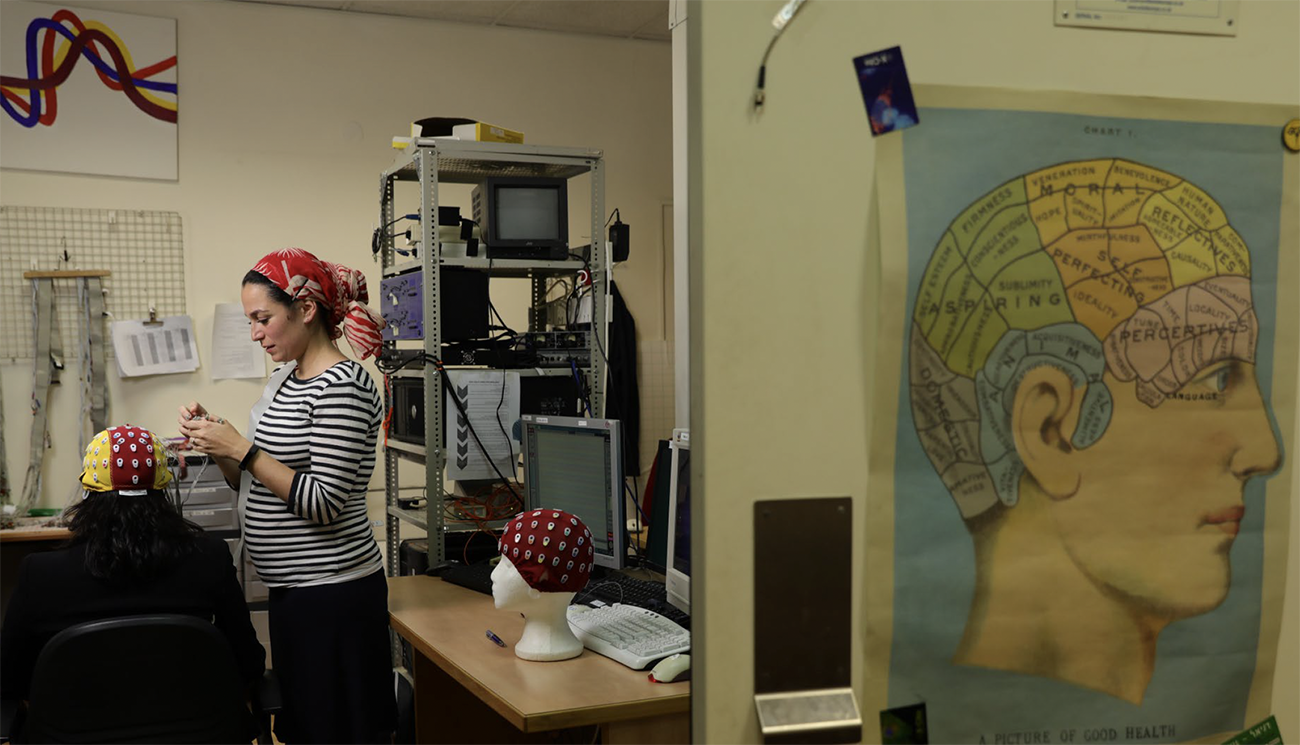

Slot machines provide Marciano with a real-time way to observe dynamic expectations and develop a deeper understand of how they relate to subjective experience. Plus, because slot machines are used frequently in gambling research, there are already validated research paradigms. To track changes in expectations, Marciano uses neuroscience techniques that can capture rapid changes in brain activity: electroencephalography (EEG) and intracranial EEG.

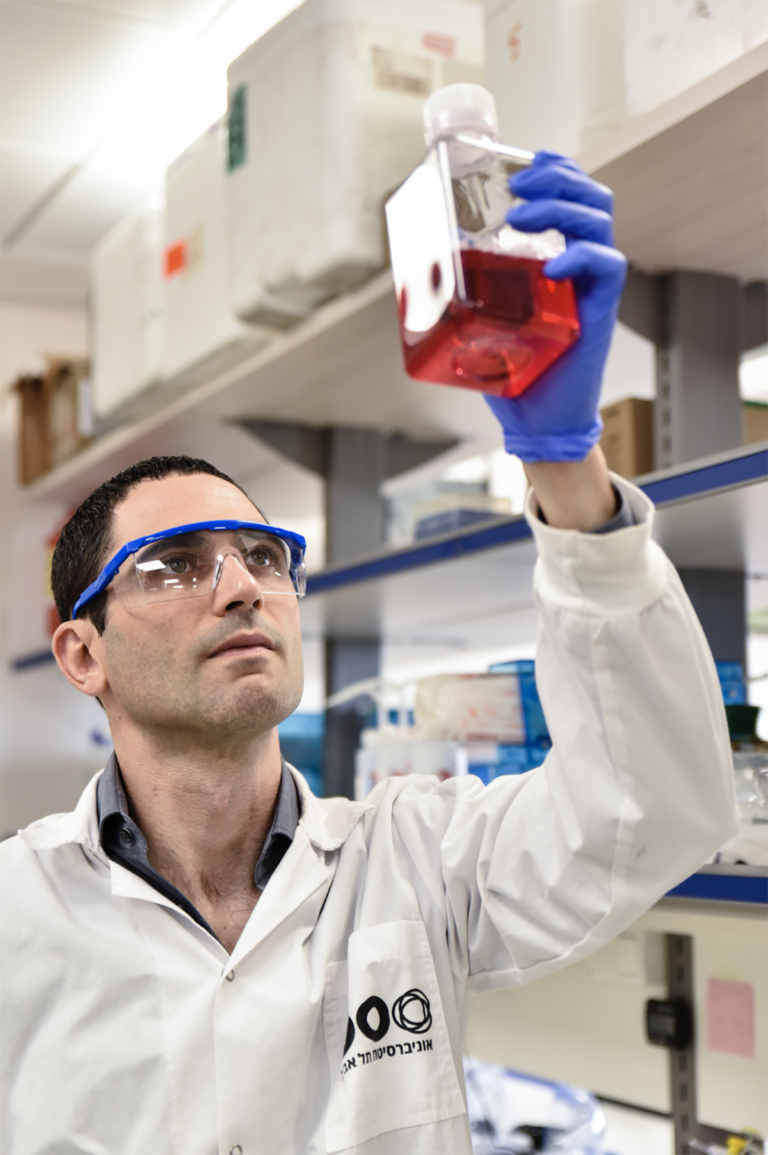

Knight’s research group works with patients who are about to undergo surgery for epilepsy. They’ve had electrodes implanted in their brains to figure out where the seizures are starting, but often have to wait for a week or so before the surgeons are sure they’ve identified the right spot. While they wait, many patients agree to take part in neuroscience experiments. The intracranial — inside-the-brain — electrodes provide high-resolution measurements of brain activity that are impossible with conventional imaging techniques, Knight explains. With a network of collaborating surgeons across the United States and around the world, his research team always has someone ready to hop on a plane whenever one of these patients is available and willing to participate. This tool gives Marciano the ability to observe how subjects’ brain activity changes on a moment-by-moment basis.

One day last fall, Marciano received data from an epilepsy patient in Oslo who had played a series of virtual slot machine games the previous day. Activity in the patient’s orbitofrontal cortex, an area that integrates information about potential rewards from other parts of the brain, “beautifully tracked” their changing expectations as the slot machine spun: a gradually swelling crescendo of hope followed by a sudden crash, in the case of near misses.

The anterior cingulate cortex, meanwhile, keeps track of prediction error: the gap between what you thought was going to happen and what actually happened. The interaction between these two brain regions — between expectation and prediction error — as the wheels spin may be what gives us the mistaken impression that we’ll win if we drop just one more quarter into the machine, Marciano suspects. But nailing down the role of other brain regions will take time and luck: the data she gets depends in part on where her volunteers’ seizures originate, which determines where the electrodes are placed. In the meantime, a series of EEG and behavioural experiments have confirmed her predictions: our expectations can change within hundreds of milliseconds. This “rollercoaster of expectations,” the ups and downs, predicts happiness ratings following gains and losses on the slot machine. Future studies with lesion and Parkinson’s patients (who often develop problematic gambling habits once medicated) will help her understand the neurobiological mechanisms at play during expectation formation.

Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel Prize–winning psychologist who helped pioneer the study of cognitive biases, was famously skeptical of our ability to overcome them. Knowing that you’re prone to certain patterns of thought doesn’t necessarily enable you to avoid them, he argued. Will learning about the near-miss effect help anyone walk away from a slot machine rather than dump more money into it? Or to navigate other situations where near misses influence our responses, from picking stocks to driving in traffic?

To Marciano, this framing of the question is too narrow. To her, there’s no doubt that understanding seemingly irrational responses like the alternative omen and near-miss effects can be used to alter behaviour. “I think the casino industry understands this very well,” she says, “and they exploit it.” But there are also broader benefits to understanding the mechanism behind biases. “The near-miss effect was just the starting point that led us to ask how we form expectations from moment to moment,” she says, “and how these expectations relate to outcome evaluation in healthy cognition and in disorders such as depression.”

Moreover, after years of studying decision-making from the perspective of economists, philosophers and psychologists as well as brain scientists, Marciano doesn’t believe we should aspire to a robotic rationality that makes every decision on the basis of its predicted utility. The changes taking place in our brains as a spinning slot machine wheel slows to a halt reflect a much larger truth about how our subjective experiences depend as much on the journey as the destination. “I think we’re now understanding that happiness is not just ‘Did I win?’ or ‘Did I lose?’” she says. “It’s also, ‘Was I surprised along the way? Did my hopes go up or down?’ Just like with a rollercoaster, focusing on the start and the end doesn’t tell you much about the experience. Looking at the turns and loops is a whole other story.”