We tend to think of architects designing inert structures, not dynamic systems. But buildings influence their users. Design produces outcomes. And perhaps nowhere is this more evident than in hospitals.

A landmark paper in 1984, written by Roger Ulrich and published in the journal Science, found that patients who saw greenery through their hospital windows needed less pain relief and fewer post-operative days in care than patients who could only see a brick wall. That paper helped spawn a field known as “evidence-based design.”

Evidence-based design explores, among other things, connections between architecture and health. It recognizes that the built environment has an impact on how a facility performs and how its users fare within it. Everything from ward layout to lighting and acoustics will have consequences related to clinical outcomes, staff performance and the well-being of patients. Some will be life-and-death. And, just as in medicine itself, medical architecture should “do no harm,” says Pilosof. In fact, she argues, medical buildings should be designed, as much as possible, to support the healing process.

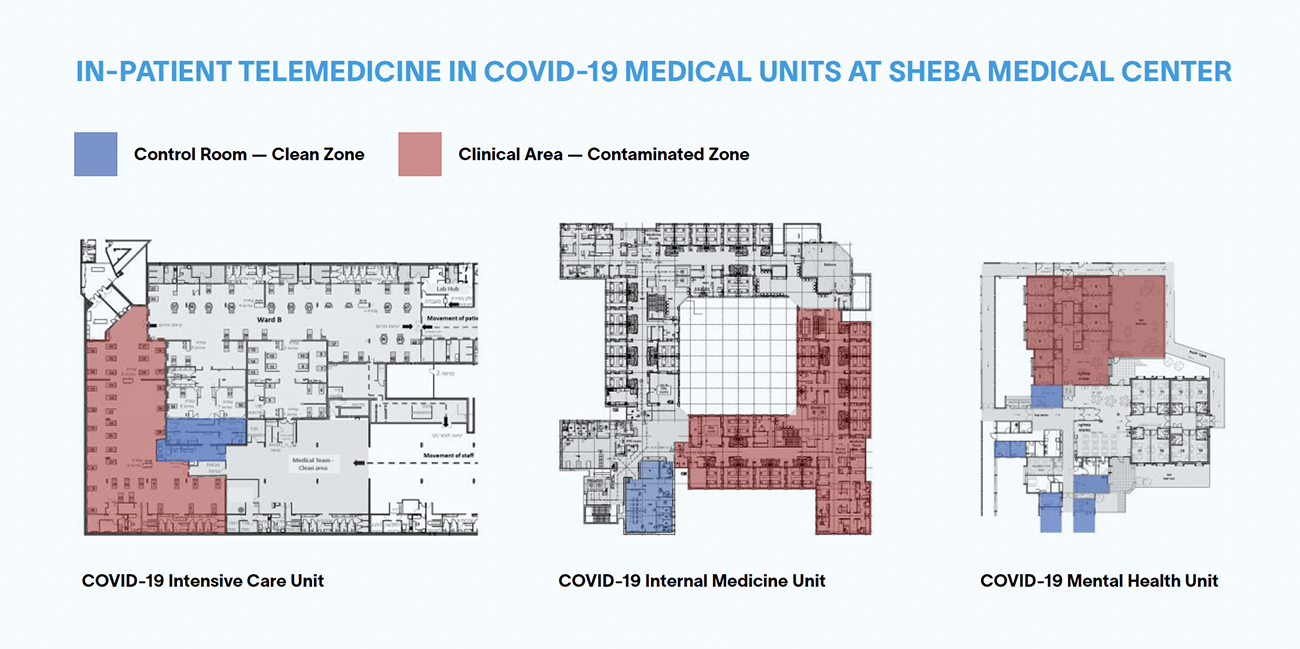

There are two central lessons from the study of Sheba’s COVID units, according to Pilosof. One is that there is great potential for so-called smart hospitals. “The hospital can really change if we start looking at how we can redesign it by using remote technologies,” she says. The other is that there are still big ethical questions to be addressed. “How do we redesign health care services,” she asks, “without compromising patient privacy and human dignity?”

Although the COVID part of her research is now complete, Pilosof continues to collaborate with Cambridge and Sheba on a project called “Hybrid models of care: Integrating physical care with virtual care.” She and her colleagues believe that hospitals will evolve from centralized monoliths that do everything inside their walls into more dispersed health care ecosystems. A transformation that’s currently underway at the Sheba Medical Center, led by its ARC (Accelerate, Redesign, Collaborate) Center for Digital Innovation, provides a perfect real-time example to study. The hospital — one of the best in the world — recently launched “Sheba Beyond” to become Israel’s first virtual hospital. Through this arm, the facility offers different kinds of care, including ambulatory services, rehabilitation and remote home hospitalization.

“We realize that in the future, physical hospitals will be used only for acute care,” says Pilosof, who became head of research in Sheba’s Innovation and Transformation Division this past September. “Remote technologies hold the potential to change the layout of medical units completely.”

Many in-hospital patient rooms will have to be transformed into intensive care rooms, for instance, which is more complicated than it may sound as they require different types of staffing and infrastructure. At the same time, many other types of patients will be monitored remotely — some within the physical building, but some elsewhere, including in their own homes. According to one vision, patients will be monitored identically, regardless of where they are located, using a tablet to access their medical data. In Sheba’s home hospitalization trial, specialists monitor patients at home using virtual technologies. (Only patients who have someone at home to help out are eligible.) If the patient’s condition worsens, they can come straight back to the same unit, bypassing the emergency department. “The team already knows them and their medical history,” says Pilosof. “The way they look at it is that the unit has both physical beds and virtual beds.” Medical professionals are happy to have access to continuous data, rather than relying on self-reports, and patients are often comforted

by the fact that they are being monitored closely.

Pilosof is currently assessing how well the project is working by conducting qualitative interviews with all of the relevant stakeholders. She has already found that interactions between medical professionals and patients’ families are being altered — in most cases, for the better. In a hospital, during rounds, doctors and their entourage typically move from room to room, and patients’ families are often excluded. In Israel, most rooms are semi-private and family members are asked to wait outside to protect the privacy of the other patient. When done remotely, however, families are invited in. “When the patient is at home, they actually ask the family to join the meeting, because they need the family to be involved in the care,” says Pilosof. “This has really shifted the relationship between the patient and the family and the medical staff.” Families are now part of the team, she says, and almost part of the staff.