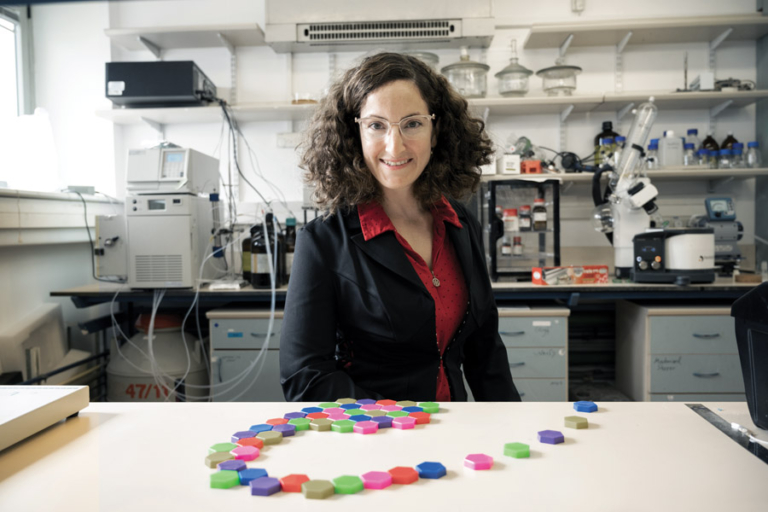

We all want to be remembered, unless it’s for something we’d rather forget. In the past, one’s transgressions — bankruptcy, fraud, infidelity, even murder—might have been recorded in newspapers and then quietly, over the years, slipped into archive obscurity. Then came the limitless memory of cyberspace. Jasmin Wennersbusch, an Azrieli Graduate Studies Fellow and PhD candidate in the Buchmann Faculty of Law at Tel Aviv University, whose research examines extraterritorial human rights protection on the internet through the lens of human rights theory and conflict of laws, finds herself pondering old concepts in a contemporary context: is it possible to be the author of one’s own life story, or to erase it and start again, in a borderless realm? Wennersbusch, who holds a Doctor of Law degree from the University of Düsseldorf as well as an LL.M. in International Law from the University of Cambridge, answers yes, but with a caveat: only if states cooperate to protect those rights and push back against Google and Facebook’s new world order.

“When we post something on Twitter or upload a new website, the content will be immediately accessible around the world and may generate conflicts in other countries. There is a disconnect between our expectations — which are rooted in the place we come from — and the borderless nature of our actions on the internet.”