In 1996, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved 53 new medications. Two decades later, after massive advances in computing technology and artificial intelligence, new DNA editing and sequencing tools, and impressive advances in basic science, that number increased all the way to … 59. And those years were outliers on the positive end; the intervening period saw an annual average of just 30 drugs getting the official stamp of approval that paves the way for distribution to patients. Bringing a drug through that process can take well over a decade and cost upward of $2 billion USD. While drug companies might undertake this arduous path for a medication expected to be taken regularly by a wide swath of patients, research often ignores rarer (or less profitable) diseases.

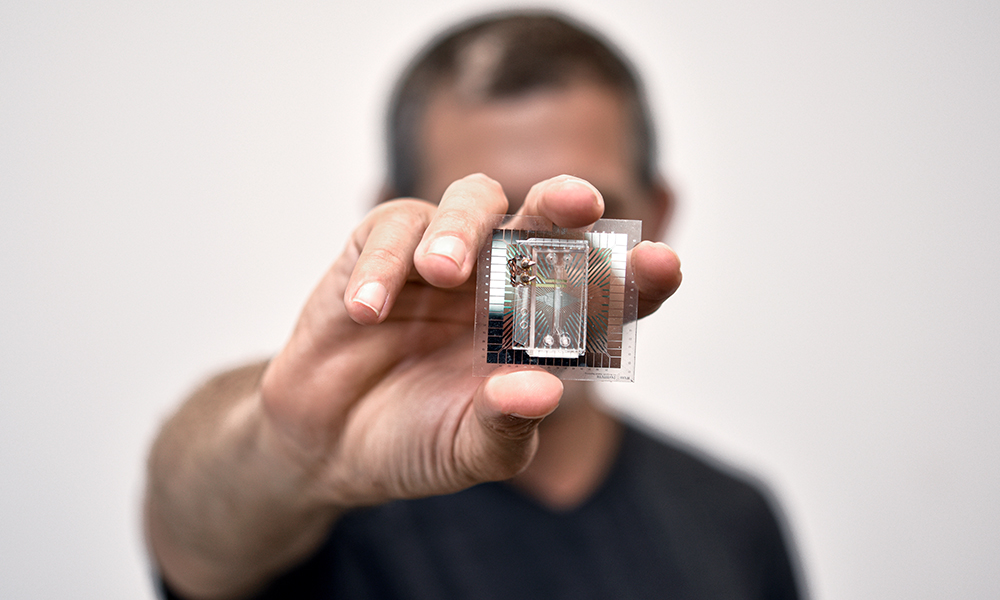

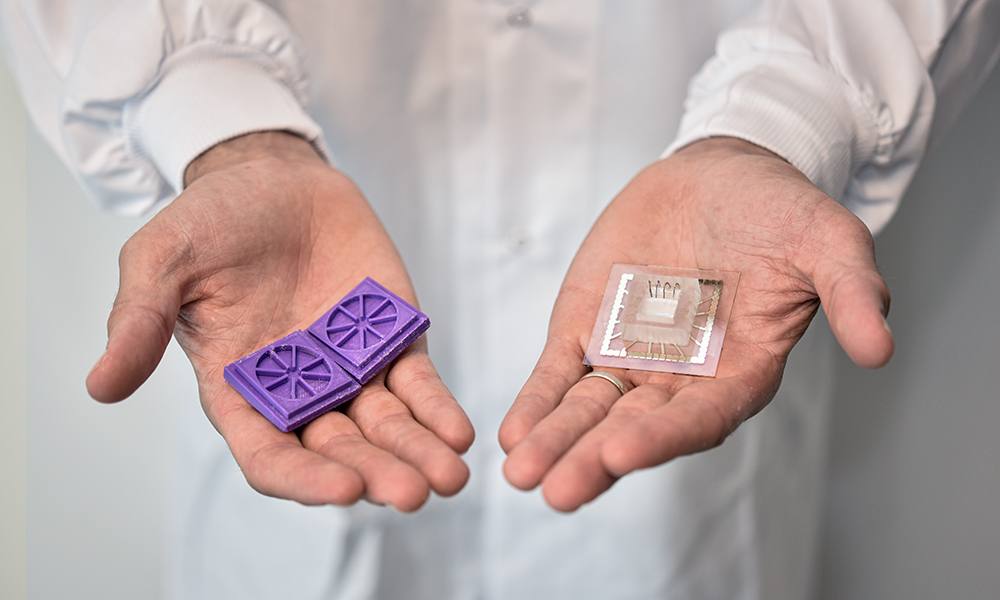

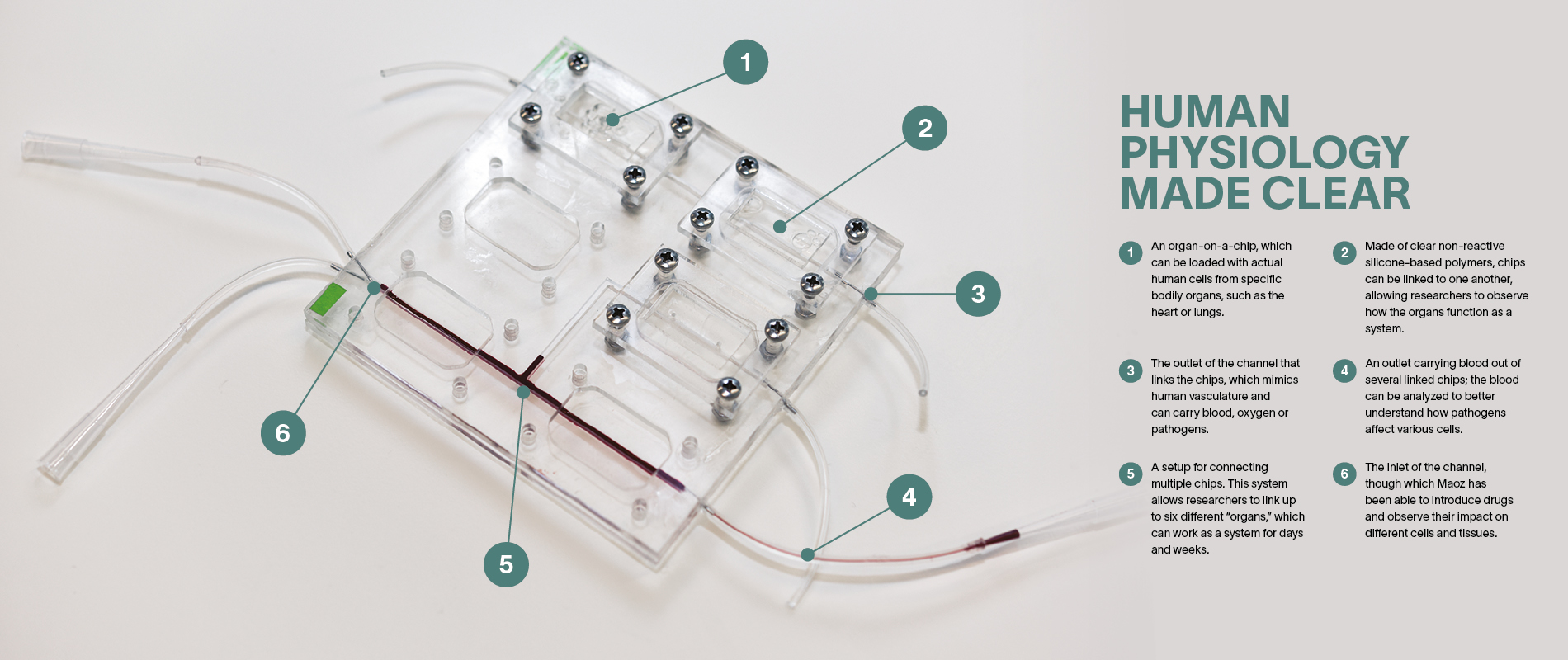

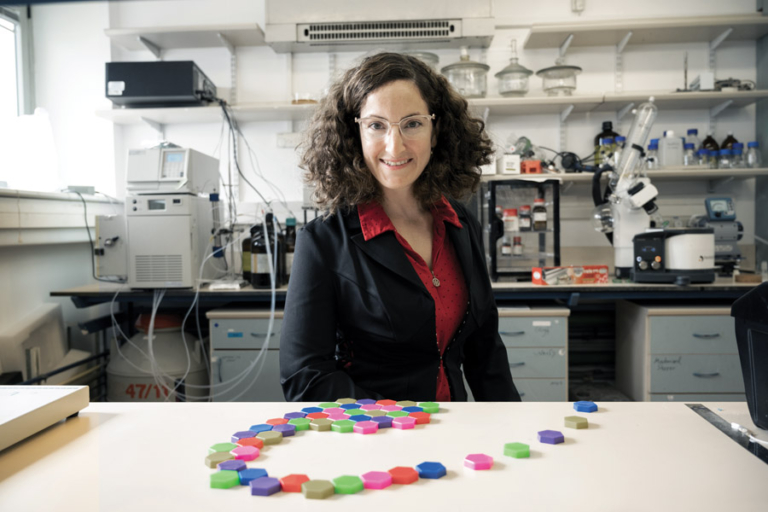

Ben Maoz wants to change all that. His secret weapon is a clear piece of plastic about the size of a USB drive. Maoz, who held an Azrieli Early Career Faculty Fellowship between 2018 and 2021, is cross appointed to the Department of Biomedical Engineering and Sagol School of Neuroscience at Tel Aviv University (TAU). Working at the forefront of biology and engineering, he and his colleagues mimic the functionality of human organs on what they call organ-on-a-chip technology.