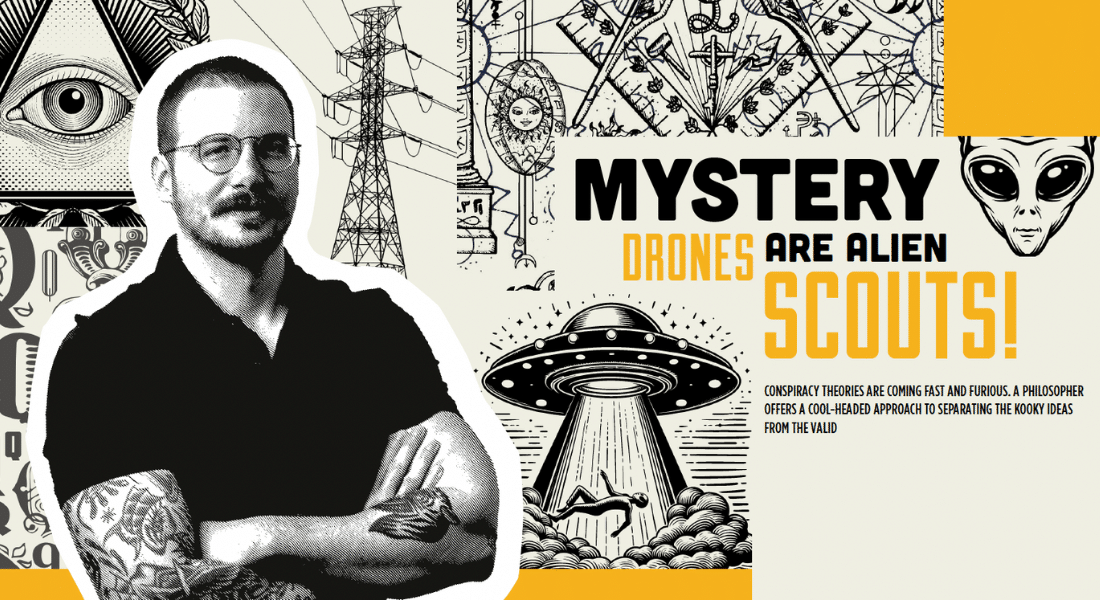

Before they were celebrities, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein were considered by some to be conspiracy theorists. As cub reporters at The Washington Post in the early ’70s, the duo suspected that United States President Richard Nixon had helped orchestrate — and cover up — a plot to wiretap the Watergate Building, headquarters of his political rivals. Of course, Woodward and Bernstein weren’t sure, at first, that any of this had happened. They were journalists, following a lead. Which is to say, they had a theory, and it involved a conspiracy. For Alexios Stamatiadis-Bréhier, there is nothing disparaging about the “conspiracy theorist” label. Sometimes, it’s a simple matter of fact. Stamatiadis-Bréhier is an Azrieli International Postdoctoral Fellow and a philosopher at Tel Aviv University. He is part of a generation of philosophers who are rethinking conspiracy theories, bringing nuance to a field that often lacks it.

Conspiracy theories, they argue, can be an annoyance — even a distraction. But, they can also be necessary components of a healthy civic culture. The trick, for Stamatiadis-Bréhier, is to figure out how to manage them — to give them the attention they deserve without succumbing to crankery.

Stamatiadis-Bréhier came by his interests in conspiracies by happenstance. As a PhD student at the University of Leeds in the United Kingdom, his main focus was the niche field of “philosophy of explanation” — an endeavour that began in earnest in the 20th century as philosophers sought to understand the nature of modern theoretical science. This corner of philosophy asks questions such as: What is an explanation? How should explanations be modelled? And what does it mean to say that X explains Y? He recognizes that these inquiries may seem pedantic to the average person. “That’s how philosophy works,” he says. “You take a seemingly simple question and abstract away from it.”

Stamatiadis-Bréhier was deep into his PhD in 2020, when COVID hit. Locked down in northern England, he became fascinated by the many theories then proliferating online. Was the virus real? Was it engineered in a lab? Were the lockdown orders the work of a shadowy cabal intent on re engineering society? “Even among reasonable people,” he recalls, “the experience of the pandemic generated paranoia and conspiratorial thinking.”

When Stamatiadis-Bréhier returned to Athens later that year, his curiosity had ballooned into all-out fascination. He started watching movies about conspiracy theories — Marathon Man, The Conversation, All the President’s Men — so often that it proved tiresome for his girlfriend. Around that time, the couple adopted a black cat and named it Zapruder. She liked the name for its quirky charm. He liked it for its connection to the notorious Zapruder film, a piece of amateur footage of the Kennedy assassination that spurred theories about a second gunman.

Like most countries, Stamatiadis-Bréhier’s native Greece has its own homegrown conspiracy theories. The country has been rocked by wiretapping cases, from the Vodafone scandal of 2004–05 that affected more than 100 Greek lawmakers and civil servants, to the Predatorgate scandal of 2022, when prominent politicians, prosecutors, journalists and businesspeople were allegedly monitored by the Greek National Intelligence Service using Predator spyware (a definitive link to the GNIS has not yet been established). The stories are extreme, but to call them farfetched would be to miss a crucial point: They are based in fact, even if many details remain unclear.