In recent months, headlines have trumpeted the news that our microbiome — the community of microorganisms that lives in and on our bodies — can be affected by factors and conditions as disparate as alcohol and artificial sweeteners. It is a familiar theme. Since the early 2000s, there has been a steady drumbeat of hype about the links between microbes and human health. Advances in DNA sequencing technology have made it possible to assemble huge catalogues of the bacteria present in any given organism. It is such an exciting and rapidly advancing field, says neurobiologist Eran Blacher, that it is easy to overlook a basic question: “What is the biological meaning of all this?”

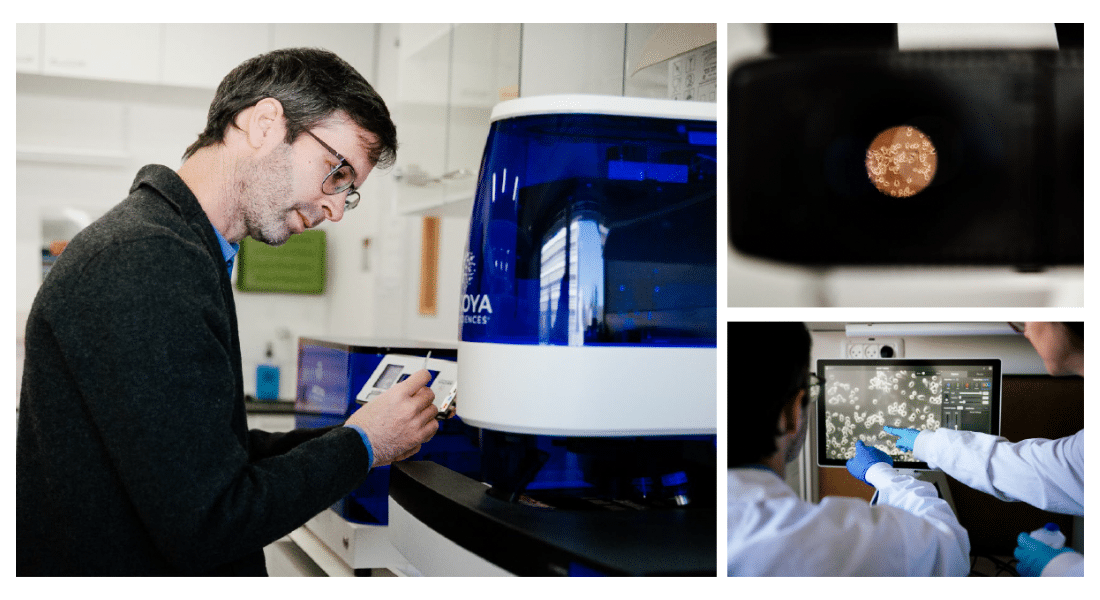

Blacher heads the Gut–Brain Axis Laboratory at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, which he established in 2023 with support from an Azrieli Early Career Faculty Fellowship. He is interested in understanding brain maladies such as Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and stroke, all of which are influenced by the two-way communication paths connecting the brain with the gut and its associated microbes. He has new findings, for example, linking stroke recovery to gut permeability (the extent to which the gut “leaks”) in aging.

But he is not convinced that solutions will take the form of fortified yogurts or probiotic pills, or that simply making lists of what organisms are present in healthy and diseased microbiomes will get us there. “We don’t want to spend our entire careers just cataloguing bacteria without knowing if they’re doing something clinically useful or not,” he says.

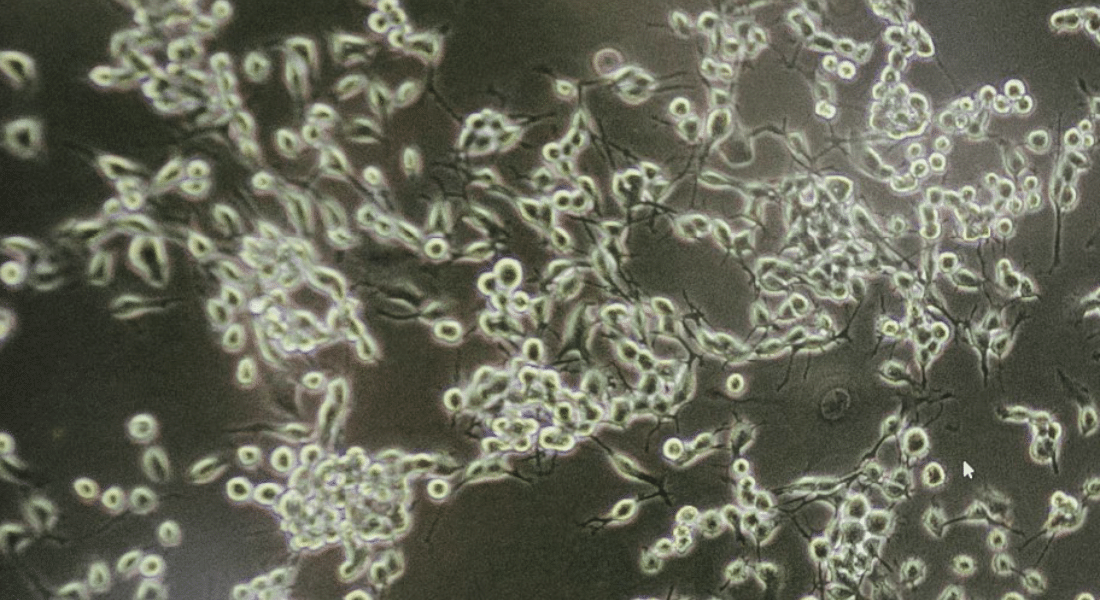

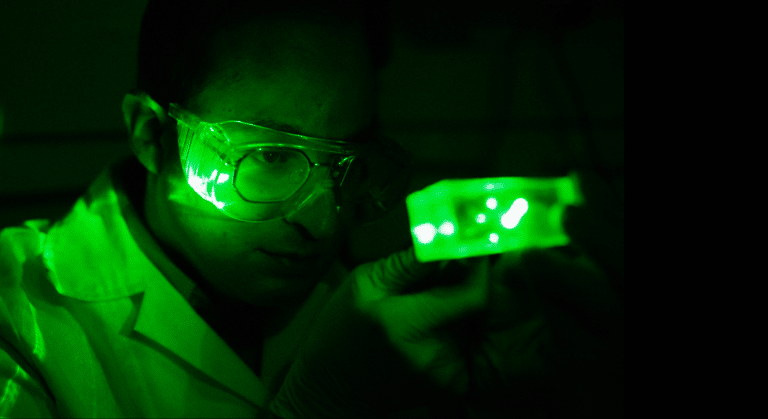

Instead, he’s pursuing a more holistic and multidisciplinary approach to microbiome research that focuses on understanding the links between form and function, as well as tracking how that changes with age. And he’s harnessing new techniques in the emerging field of spatial biology to make a big bet on the future of microbiome research: that it’s not just which bacteria are present that matters, but also where they are.