Smell may be the most elusive of all senses, and the most intimate.

The sense of smell helps us identify odorants, but that’s not all. Because smell and emotion are stored as a single memory, odours add an emotional dimension to events and influence our mood and thoughts. Yet, while scientists can tell us so much about the inner workings of hearing, vision, taste and touch, it is only in recent decades that smell has attracted the attention it deserves.

Modern-day interest can be traced to 1991, when molecular biologists Richard Axel and Linda Buck announced they had identified 18 of the genes that control odour receptors; the milestone showed young neuroscientists a pathway to a rich field of research. Advances in the natural sciences have inspired experts in the humanities to incorporate the study of smell into their own work.

We may still not know why a particular molecule smells the way it does; intriguingly, the chemical structure of a molecule says little about its odour. But we are learning more about the ways the olfactory system operates and its overall role.

Scientists, for example, have developed a molecular-level, three-dimensional model of how an odour molecule activates a human odorant receptor, a crucial step in understanding the sense of smell. Labs with expertise in organic chemistry, software engineering, machine learning and other disciplines are developing digital smell technology that may lead to devices that can help clinicians diagnose disease and allow users to sense and transmit odours via the internet.

The arts are also recognizing the value in engaging the sense of smell. A growing number of museums are creating “scentscapes” to provide visitors with a visceral experience. The most pungent of them all is Brunel’s SS Great Britain, a museum in Bristol, England, that immerses visitors in the experience of travelling on a Victorian-era steamship with the help of odours that suggest smoky bacon, rum, urine, vomit and horse manure.

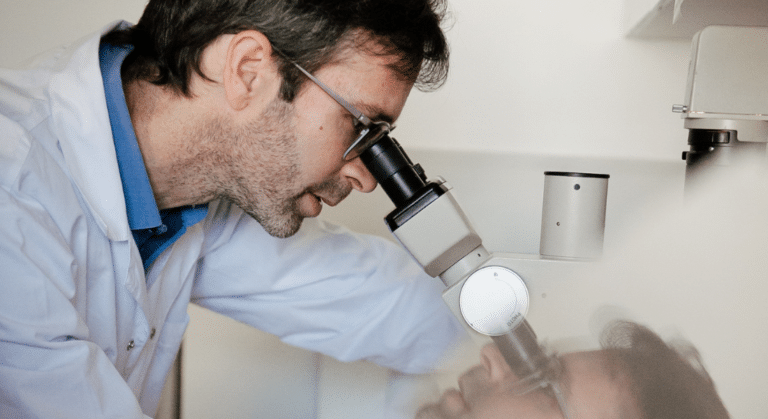

Clearly, for the sense of smell, everything is coming up roses, and that suits Michal Andelman Gur and Tal Yehezkely just fine. Andelman Gur, a former Azrieli Graduate Studies Fellow, is an MD and a PhD student and neurobiologist in the Weizmann Olfaction Research Group at the Weizmann Institute of Science. Yehezkely is a scholar of comparative literature and a current Azrieli Graduate Studies Fellow pursuing research at the School of Cultural Studies at Tel Aviv University.

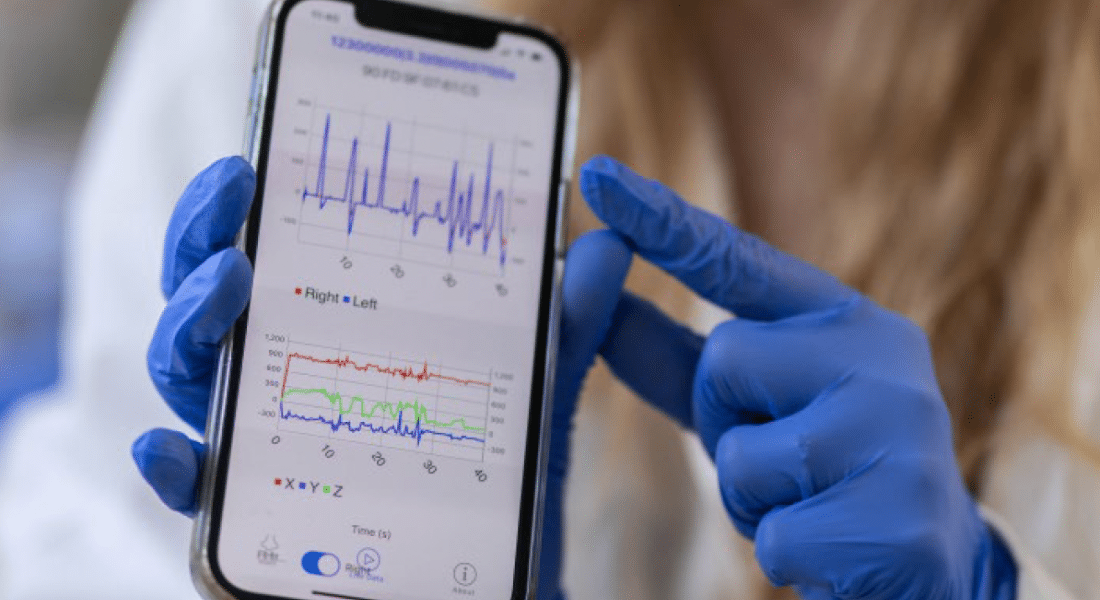

Both Andelman Gur and Yehezkely are making their names as up-and-coming smell investigators. Andelman Gur is developing a way to use the sense of smell and patterns of respiration as biomarkers for Parkinson’s disease, a movement disorder of the nervous system. Yehezkely is using smell as a marker as well, though within the world of literature. She explores how writers use smell to communicate the struggle of outsiders, a sensitive theme often difficult to express.

Aperio editor Alan Morantz spoke with Andelman Gur and Yehezkely to explore why smell is now such an alluring topic of enquiry.

Alan Morantz: Michal, you’re trained as a medical doctor, and Tal, you’re trained as a philosopher. How did you end up studying the science of smell or exploring its literary merits?

Michal Andelman Gur: For me, smell and respiration are windows to the brain, and that’s why I chose to study them. The sense of smell is the only sense with a direct pathway to the brain. It’s closely linked to the brain centres of memory and emotions that are called the hippocampus and amygdala. And there’s also evidence that respiratory patterns are closely linked with brain activity, something we call the “sniffing brain.”

AM: When did you first realize there was something about smell worth studying?

MAG: I remember when I was in med school, we were taught about Parkinson’s disease, that it’s a movement disorder. But only afterwards, I heard that many years before the motor symptoms appear, patients lose their sense of smell. And I thought this was so strange, and it has something to do with the brain in a way that I didn’t think of until that moment. That got me curious.